In the early days of August, 1914 the world held its breath as the major powers of Europe plunged into war. The assassination of Austria’s Archduke in June of that year resulted in a failed ultimatum against Serbia, the nation blamed for the murder. On July 28, 1914 Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. This action set in motion the alliances that would ultimately begin what would become the First World War.

For years Germany had been preparing for war against its main rival and neighbor, France. The Germans realized that the existing alliance between France and Russia put them right in the center of the action should war ever erupt. This meant that Germany would potentially end up fighting a two front war or battles on both its eastern and western borders. A two front war would significantly weaken the German army by forcing a division of their forces to protect both borders.

In 1905, Count Alfred von Schlieffen developed a plan to rush into France through Belgium, conquer France within weeks and then move on Russia. The plan depended on several factors and assumptions:

- The German advance would be fast

- The French army was weak

- Russia would be slow to mobilize, providing time to conquer France

The plan would essentially work like this: German forces would sweep through Belgium and into France, encircle and defeat French forces, and then race to Russia via Germany’s vast railway system. The plan was perhaps the best Germany could do at the time. One major shortcoming, however, was the failure of Schlieffen’s successors to update the plan and consider evolving factors in the years leading to World War I.

On August 4, 1914 the German army invaded Belgium, disregarding their declared neutrality and forcing them to join the Allies. The invasion also prompted Great Britain to declare war on Germany. In doing so, the British made good on their promise to uphold Belgian neutrality.

Initially facing strong resistance in the Belgian city of Liege, the Germans and their heavy artillery pushed through and overran most of the country by the end of August. Battles would continue within Belgium through October, culminating with the First Battle of Ypres. For the most part, Belgium was now a German occupied country and would remain so throughout the war. In late August, the Germans divided Belgium into three administrative zones, each overseen by German military officers and officials.

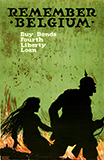

British propaganda that reads- The Germans have broken their pledged word and devastated Belgium. Help to keep your Country's honour bright by restoring Belgium her liberty.

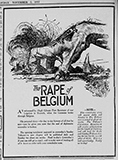

Moving through Belgium, German soldiers were under orders to respond to any resistance from Belgian civilians. This order led to one of the longest-lasting controversies of the war. It is well known that once the invasion began, German soldiers were actively shooting civilians and burning their homes. Whether or not the Belgian civilians were involved in any initial resistance is hard to know with certainty. It is possible that German soldiers had trouble differentiating civilian attacks from those led by Belgian soldiers as they fought within the Belgian towns.

On August 23, the Germans killed 674 civilians (including women and children) in the city of Dinant. A few days later, German soldiers in Louvain unknowingly engaged each other in a nighttime firefight. The Germans were convinced they had been attacked by civilians and set about destroying and looting the Belgian city where more than 200 people would be executed.

It is estimated that over 5,000 Belgian civilians were killed during the invasion of Belgium. The brutality of the German army gave rise to allied propaganda that depicted the Germans as ruthless and barbaric “Huns.” The allies exploited the treatment of Belgians in their propaganda campaigns throughout the four year war. Ultimately, stories of German brutality would begin to turn potential allies and neutral countries toward alliances with France, Britain, and Russia.

-WD

Additional Propaganda Samples

British propaganda |

British propaganda |

British propaganda |

US propaganda |

US propaganda |

Related Lesson Plans

Further Reading

- The Schlieffen Plan

- BBC- The Schlieffen Plan

- First World War.com: War Plans

- Schlieffen Biography

- Modern Re-examination of the Schlieffen Plan

First Posted: 07/01/2014